Autism – The theory of mind account. Autism, also referred to as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is defined as a pervasive neurodevelopmental condition. It involves moderate to severely dysfunctional social skills and socialisation, restrictive and disruptive behaviours, and repetitive and obsessive interests (Pennington, Cullinan & Southern, 2014). The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria are the presence of all 3 deficits in: Social emotional reciprocity; in Nonverbal communication; and in Developing and maintaining social relationships. In addition, 2 of these behaviours and interests must be present: Abnormally restricted interests; Inflexible routines and rituals; Motor mannerisms – rocking; Preoccupation with parts of objects.

The prevalence of autism has dramatically increased over the last two decades with rates rising, in the US, from 1 in 1000 children to 1 in 88 children. Reasons for this massive growth has been attributed to changes in the diagnostic criteria.

Historically, the disorder, featured in the medical literature of the nineteenth century through cases like Victor, The Wild Boy of Aveyron in France, who had severely underdeveloped social and communication skills. In the 1930s and 1940s, Dr Leo Kanner authored a definitive paper titled “Autistic disturbances of affective contact” (Markham, 2011). In these extracts of Kanner’s descriptions of autistic children you get a distinct impression of the disorder:

“When taken into a room, he completely disregarded the people and instantly went for objects…

He never looked up at people’s faces…

It was as if he did not distinguish people from things…” (1943).

The definition and diagnosis of the disorder continues to evolve, and as mentioned the diagnostic criteria have been widened to include milder forms of autism like Asperger’s Syndrome.

Some of the non-diagnostic features of autism include: intellectual disability; memory problems; language impairments; reading difficulties; attention deficit; epilepsy; motor discoordination; sensory hypersensitivity; dietary issues; and the infamous savant skills (Baron-Cohen, 1997).

Theory of Mind

The Theory of Mind Account is the ability to comprehend and predict behaviour according to the underlying mental states in oneself and in others (Schuwerk, Vuori & Sodian, 2014). The fact is that other people’s minds are invisible to us, so we develop a theory of mind that states that other people’s mental state may be different from our own. Simon Baron-Cohen writes that we, “mindread all the time, effortlessly, automatically, and mostly unconsciously” (1997). However, children with autism are ‘mindblind’ to the mental states of others, they do not possess a theory of mind regarding those around them.

The theory of mind hypothesis was developed by Baron-Cohen in the 1980s and seeks to provide a “unified cognitive explanation” for autism’s main social and communication symptoms (Tager-Flusberg, 2007). In 1985, Baron-Cohen, Uta Frith and Alan Leslie first proposed that three of autism’s key symptoms, abnormal social development, communication development dysfunction, and abnormalities in pretend play, may be caused by their inability to ‘mindread’ (Baron-Cohen, 1997). Baron-Cohen produced a model for how human beings evolved their acute mindreading skills.

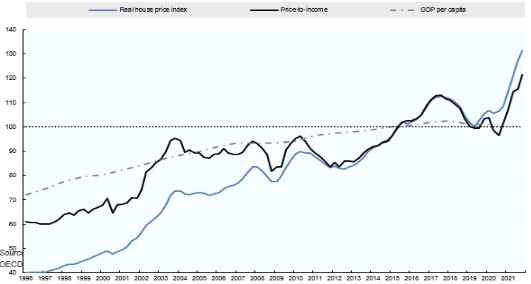

Fig. 1 (Baron-Cohen, 1997).

In the Fig.1 above, ID stands for Intentionality Detector, which is our basic ability to immediately perceive outside agencies and their goals or desires. These agencies have self-propelling properties and are observed through our senses. An agency may be detected as a non-random sound, or an unexpected touch. We perceive someone or something and we instantly speculate on the agent’s goals and desires. This is hardwired into our brains for survival and recognising potential dangers. The second mechanism in this model is Eye-Direction Detector (EDD), which is a vision only sensory ability. It detects the presence of eyes and where those eyes are looking. It is acutely sensitive to whether the eyes of someone or something are looking into our own eyes. We all know that funny feeling when you intuit that someone is staring at you, and when you catch their eye contact, it is often quite disturbing. Eye contact arouses physiologically stimulatory responses within us when we become aware of it. Baron-Cohen stresses the importance that we as human beings attach to eye contact, that babies seek out and respond positively to eye contact with another human being. Both ID and EDD are described by Baron-Cohen as dyadic, as they are limited to the intentional relationship between agent and object or agent and self. The third mechanism is Shared Attention Mechanism (SAM), and this allows triadic representations. There is now a third level of awareness, a shared interest in the same object or agency, “Mummy see that I see the bus” – for example (Baron-Cohen, 1997). SAM relies heavily on EDD; confirming eye contact as an essential human sensory ability for sharing perceptual awareness. The fourth mechanism is Theory -of-Mind Mechanism (TOMM), which was first coined by Alan Leslie in 1994. TOMM is our system for the inference of mental states from behaviour in others. We employ a theory of mind, to explain the actions and attitudes perceived in those around us. Baron-Cohen emphasises the ‘pretend play’ stage that toddlers go through, and that this is the forerunner to being able to imagine mental states.

False Belief Task

Research studies employing the false belief task have observed that when children under the ages of three or four are shown pictures representing, for example, two characters called Sally and Anne. In a sequence of scenes, Sally hides her ball in a basket and exits the scene, then Anne takes the ball from the basket and places it in a box. The child is then asked where will Sally look for her ball when she returns. In most cases these young children will assume that Sally will know what they have seen and look for the ball in the box (Tager-Flusberg, 2007). Children over four years, generally, understand that Sally did not see Anne move the ball to the box and will look in the basket where she left it originally. Most autistic children older than four years, however, failed this test. The rates are about 80% to only 20% pass marks in favour of non-autistic children from these false belief tests. These tests, and others like it, were part of the research upon which the theory of mind hypothesis was developed. It proposes that autistic children have a deficit in acquiring the normal “mindreading” abilities that the rest of us have. They have no theory of mental states, outside of their own mental state, thus their impairments in social reciprocity and communication can be explained on this basis.

In a range of other tests, researchers have sought to understand, mental disorders like autism and how they affect cognitive abilities in those with the condition. Visual perspective taking, picture sequencing, and false photographs tests have shown a variety of results. They indicate that autistic children can understand sabotage but not deceit. Autistic people, generally, do not modify their account of events, even when talking with listeners who have not witnessed the events for themselves. There is a failure to differentiate between old and new information, and this can be revealed by their use of definite articles and pronouns during conversation.

Executive Functions & Theory of Mind

Executive functions are: our ability to plan; to hold information in our memories whilst complete other tasks; our shifting response set; our ability to inhibit our responses and information. These executive function abilities are located in the frontal lobe parts of the brain. Executive functions are impaired in those with autism (Pellicano, 2010). Performing Theory of Mind tests directly involve executive functions. To have a theory of mind, one must overcome the saliency of reality. Imagining, believing, pretending, knowing, deceiving, dreaming, guessing and thinking are all dependent upon that mental leap (Baron-Cohen, 1997).

Critical Evaluations of Theory of Mind

Theory of Mind (TOM) is the preeminent cognitive theory for the neurodevelopmental condition known as Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Despite the two-decade body of evidence that the impairments associated with ASD are due to the absence of TOM in those with ASD, there are questions as to whether TOM has produced treatments that are effective in improving social behaviour, empathy and greater understanding in tested autistic subjects (Begeer, Gevers, Clifford, Verhoeve, Kat, Hoddenbach & Boer, 2011). Some within the scientific community, whilst acknowledging that interventions have improved TOM skills of individuals with autism, are questioning the poor quality of the research into the effectiveness of the treatment programs based on TOM training (Scheeren, de Rosnay, Koot & Begeer, 2012). Much of this training focuses on building awareness of the subjective mental states operating within the individual with autism and those of the people around them. This includes ‘picture-in-the-head teaching’; ‘thought-bubble-training’ and ‘social cognition’.

The question whether TOM explains all the impairment associated with ASD, is another pertinent one to ask. Does TOM explain the rocking motor mannerisms in some individuals with severe ASD? Does it explain the inflexible routines and rituals inherent in many on the spectrum? Are the abnormally restricted interests and the preoccupation with the parts of objects due to their mentally isolated existence or are these behaviours caused by something else? All of these questions have not been conclusively answered by TOM.

©Robert Hamilton

References

S, Baron-Cohen, (1997), Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind, MIT Press, Cambridge.

S, Begeer, C, Gevers, P, Clifford, M, Verhoeve, K, Kat, E, Hoddenbach & F, Boer, (2011), “Theory of Mind Training in Children with Autism: A Randomized Controlled Trial”, Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 41 (8), 997-1006.

E, Markham, (2011), Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development, ), S, Goldstein & J, Naglieri (eds), 176-182, http://link.springer.com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_248 Viewed 8 January 2017.

E, Pellicano, (2010), “Individual Differences in Executive Function and Central Coherence Predict Developmental Changes in Theory of Mind in Autism”, Developmental Psychology, Vol 46 (2), 530-544.

M, Pennington, D, Cullinan and L, Southern, (2014), “Defining Autism: Variability in State Education Agency Definitions of and Evaluations for Autism Spectrum Disorders”, Autism Research and Treatment, Vol 2014, Article ID 327271, https://www.hindawi.com/journals/aurt/2014/327271/cta/ Viewed 10 January 2017.

T, Schuwerk, M, Vuori & B, Sodian, (2014), “Implicit and explicit Theory of Mind reasoning in autism spectrum disorders: The impact of experience”, Autism, Vol 19, Issue 4, (2015), http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1362361314526004 Viewed 12 January 2017. Viewed 8 January 2017.

A, Scheeren, M, de Rosnay, H, Koot & S, Begeer, (2012), “Rethinking Theory of Mind in High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder”, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, And Allied Disciplines, Vol 54 (6), 628-635.

H, Tager-Flusberg, (2007), “Evaluating the Theory-of-Mind Hypothesis of Autism”, Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol 16, Issue 6, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00527.x?legid=spcdp%3B16%2F6%2F311&patientinform-links=yes Viewed 10 January 2017.