by Robert Hamilton

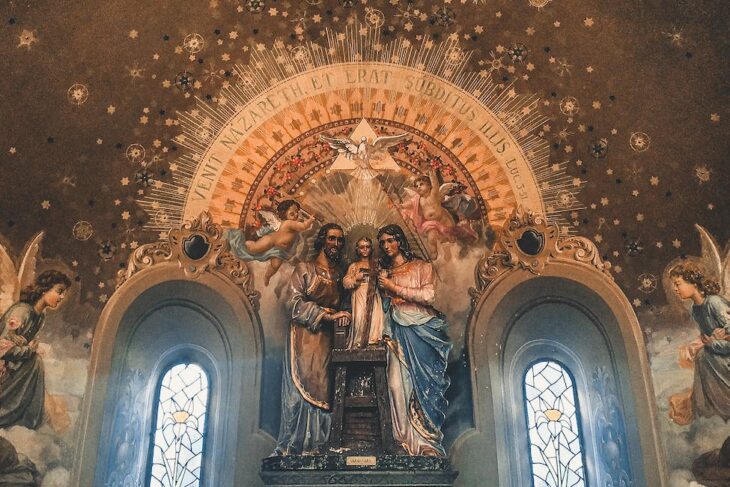

The Great Persecution began in AD303, during the Imperial power sharing known as the ‘tetrarchs’. [1] It followed a prolonged time of peace and prosperity, enjoyed by the Christian Churches, and their followers, throughout the Roman empire; this period began with Gallienus’ Edict of Toleration in 261. [2] Eusebius, in his introduction to his Book 8, of The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, rhapsodises about how good these times had been.[3] In Eusebius’ own account of the persecution of the Christians, he suggests, that it was the early Christian church leaders themselves, who were responsible for bringing down, something like the wrath of God, executed at the hands of the Imperial Roman forces. Eusebius states, that it was the infighting and theological disputes between both church leaders and laymen, which led to their apparent ‘fall from grace’.[4]

Eusebius: The Great Persecution

Why would Eusebius blame the victims themselves, many of whom experienced such terrible physical torture and death at the hands of the Roman Imperial forces? In the age of rhetoric, Eusebius is crystal clear in his apportioning of blame to these early Christian bishops, priests and vociferous laymen. Perhaps, in his ecumenical history of the church, he is selectively identifying those who belong in the political camps of later prominent church figures, like Athanasius and other anti-Arian church leaders. Those who refused to compromise over these theological issues, as Constantine so desired, when attempting to unite the fourth century Christian Church under the auspices of the Roman empire.[5] As Eusebius is rewriting sections of this history around 311-325, it is being written to influence contemporary church politics.[6] Eusebius also writes his history in a heavily biased manner toward the Christians and their god, as shown by his quoting of the prophets from the old testament, so as to contextualise the Great Persecution, under the emperor Diocletian, as actually being part of the Christian god’s divine plan.[7] Eusebius offers no contradictory viewpoints, within his history, and his language fans the flames of fanatical belief.[8] His history is about empowering the position of the Christian faith within the Roman empire, during Eusebius’ time, and for posterity.[9]

Continued in Roman and Greek History by Robert Hamilton

©Robert Hamilton

[1] Cameron. Averil, The Mediterranean World In Late Antiquity, (second ed), Routledge, 2012, P – 12 “Traditionally, and certainly in English-speaking scholarship since Jones’ Later Roman Empire, the ‘later Roman empire’ has been thought of as beginning with the reign of Diocletian (284-305). A strong division was made between the mid-third century, seen as a time of civil strife, usurpation and financial crisis manifested in debasement of the coinage and spiralling prices, or even the virtual collapse of the monetary economy, and the era which followed, when policies associated with Diocletian led to greater bureaucratization, attempts to control prices by law, an attempted power-sharing between two Augusti and two Caesars, collectively known as the ‘tetrarchs’, and a new division of the provinces and separation of civil and military rule, together with a much increased pomp and ceremony surrounding the imperial court (an Oriental despotism).”

[2] Watson, Alaric. “Introduction: The third-century crisis (part 1 of 2)” in Aurelian and the Third Century , Watson, Alaric , 1999 , P – 18 “A few years after Decius’ death, the emperor Valerian instigated a fresh call to sacrifice. This time the edict was directly targeted at the Christians. A new and more brutal wave of persecution followed. But such coercion signally failed to achieve its aim and Valerian’s son and successor, Gallienus, put an immediate stop to the persecution. The same futility awaited the great persecution at the turn of the next century. The scale of the martyrdoms and of the heroism they entailed earned the faith a new respect and even added to its appeal. Ironically, in the long term, the persecutions may thus have contributed to the spectacular success and ultimate triumph of Christianity.”

[3] Keresztes, Paul. “The Imperial Roman government and the Christian church. II, From Gallienus to the great persecution” in Aufstieg und Niedergang der Romischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung (Series II) , Temporini, Hildegard , 1980 , P-376 “The deep serenity of the post-Gallienus era is most aptly characterized by Eusebius in his report on the truly phenomenal success of the Church in the Empire before the eruption of the Great Persecution. Eusebius’ description of the freedom of the Christian Church and the unprecedented recognition of it by local and Imperial authorities during this period is certainly not exaggerated. Christians, according to the Church Historian, became governors; people in Imperial households became Christians and practiced their religion openly, Christians were prominent in the Imperial service; the leaders of Church were honoured by governors; the number of Christians increased greatly; and many new churches were built.”

[4] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, Book 8, (trans G.A. Wiliamson), Penguin Books, P – 257 “But increasing freedom transformed our character to arrogance and sloth; we began envying and abusing each other, cutting our own throats, as occasion offered, with weapons of sharp-edged words; rulers hurled themselves at rulers and laymen waged party fights against laymen, and unspeakable hypocrisy and dissimulation were carried to the limit of wickedness.”

[5] Frend, W. H. C. “The failure of the persecution in the Roman Empire” Past and Present , 16: , 1959 , P-10 “But within the Christian camp, contemporaries were already noting the presence of deep rifts (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, VIII. i. 9). And these, in the very hour of the Church’s triumph were to break out in the Donatist and Arian controversies which were to dominate its life for the next century.”

[6] Grant, Robert McQueen. “The fifth theme: Persecution and martyrdom” in Eusebius as Church Historian , Grant, Robert McQueen , 1980 , P-123 “The situation was hard to write about. Eusebius admired heroism but not suicidal heroism. He favoured the state but not at the expense of the Church. He was opposed to the rigorist Novatianists (V!. 42-6), Meletians (presumably envisaged in Mart. Pal. 12), and Donatists (subject of Constantine’s letters cited in X. 5. 18-6. 5), but not to the martyrs among them. He therefore did not precisely identify those who were carried away by ‘the lust for power’ and therefore took part in ‘the rash and unlawful ordinations and the schisms among the confessors themselves’, “

[7] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 257 “Then, then it was that in accordance with the words of Jeremiah, the Lord in His anger covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud, and cast down from the Heaven the glory of Israel; He remembered not the footstool of His feet in the day of His anger, but the Lord also drowned in the sea all the beauty of Israel, and broke down all his fences.” 1 A conflation of parts of Lam. Ii 1-2 with Ps. 1xxxix. 40.

[8] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 271 “In these trials the splendid martyrs of Christ let their light so shine over the whole world that they everywhere astounded the eyewitness of their courage – and small wonder: they furnished in themselves unmistakable proof of our Saviour’s truly divine and ineffable power.”

[9] Croke, Brian. “The origins of the Christian world chronicle” in History and Historians in Late Antiquity , Croke, Brian; Emmett, Alanna M. , 1983 , P- 116-131 “Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260-340) was, as he himself claimed and as was acknowledged by later writers, the first to establish the format and style of the Christian world chronicle. His Chronicle, first published in the 280’s and updated c. 326 was translated into Latin by Jerome (c. 345-419) and continued to 387. Subsequent writers in the West continued Jerome and each other in order to keep the record continuous and contemporary, so that the chroniclers, like the church historians, constituted a kind of ‘diachronic syndicate’. Likewise in the East, Eusebius’ Chronicle formed the fountainhead of a long tradition of chronographic writing at Constantinople, and its Armenian and Syriac translations greatly shaped the development of chronicle writing in these languages. At the other end of the known world, in Ireland, Jerome’s translation provided the backbone of the earlier Irish annals.”

[10] Lactantius, De Mortibus Persectorum, (trans – J.L. Creed) Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1984, P -11 “Diocletian was an author of crimes and a deviser of evils; he ruined everything and could not even keep his hands from God. In his greed and anxiety he turned the world upside down.”

[11] Frend, W. H. C. “The failure of the persecution in the Roman Empire” Past and Present , P – 15 “The Christians were told that they were not being asked to give up their own religion, but simply to pay respect to the gods on whom the welfare of the Empire depended.”

[12] Watson, Alaric. “Introduction: The third-century crisis (part 1 of 2)” in Aurelian and the Third Century , P – 17 “Christianity was a different matter. For Christians, their religious beliefs were incompatible with any other religious activities, including, for example, those of the imperial cult. Due to the integration of religious beliefs and practices within the socio-political fabric of daily life in the empire, this had an impact far beyond what in today’s terms might be seen as the religious sphere per se. For many pagans in the third century, Christianity posed a threat to the social, political and religious order of the world, wholly out of proportion to the numbers involved.”

[13] Lactantius, De Mortibus Persectorum, (trans – J.L. Creed), P -21 “But the Caesar was not content with the provisions of the edict: he prepared to assail Diocletian by other means. In order to drive him towards a policy of really ruthless persecution, he set fire to the palace by means of secret agents; and when part of it had been burnt down, the Christians were denounced as public enemies; the blaze at the palace became a blaze of hatred against the Christian name. The Christians, it was said, had formed a conspiracy with the eunuchs to the kill the emperors, and the two emperors had almost been burnt alive in their own palace.”

[14] Potter, D. S. “The economic and political situation of the Roman Empire in the mid-third century AD” in Prophecy and History in the Crisis of the Roman Empire: A Historical Commentary on the Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle , Potter, D. S. , 1990 , P -43 “For the Christian Church it caused a terrible crisis of authority as various bishops and their flocks reacted to it in different ways. Some Christians, such as Pionius in Smyrna, saw it as offering a splendid opportunity for martyrdom. Others thought that they should simply obey the order and obtain a libellous, others thought that they could evade the order by obtaining a fake libellous, and still others thought that they should refuse to obey, but try to stay out of the way of local officials until the excitement died down.”

[15] De Ste. Croix, G. E. M. “Aspects of the ‘great’ persecution” Harvard Theological Review , 47:2 , 1954 , P- 75 “The First Edict (hereafter referred to as ‘E 1’) was apparently issued (datum) on the 23rd February 303, on which day the church opposite the imperial palace at Nicomedia was dismantled.”

[16] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 261-262 “In the city named above (Nicomedia), the rulers in question brought a certain man into a public place and commanded him to sacrifice. When he refused, he was ordered to be stripped, hoisted up naked, and his whole body torn with loaded whips till he gave in and carried out the command, however unwillingly. When in spite of these torments he remained as obstinate as ever, they next mixed vinegar with salt and poured it over the lacerated parts of his body, where the bones were already exposed. When he treated these agonies too with scorn a lighted brazier was then brought forward, and as if it were edible meat for the table, what was left of his body was consumed by the fire, not all at once, for fear his release should come too soon.”

[17] Barnes. D. Timothy, Constantine and Eusebius, Harvard University Press, 1981, P – 157 “We decided to make no mention of those who have been tempted by the persecution or have made utter shipwreck of their salvation ( 1 Timothy 1:19) and by their own decision were plunged in the depths of the sea; we shall add to the general history only those things which may be profitable, first to ourselves, and then to those who come after us.” That is a hagiographer or a panegyrist speaking, not a historian. By his own admission, Eusebius has produced not a history of the persecution between 303 and 311 but a “summary description of the sacred conflicts of the martyrs of the divine word.” Apostasies and dissension within the Church he consigns to oblivion, for moral or didactic reasons.”

[18] Hamilton. Robert (personal reminiscence at St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church, WA, 1971) “Indeed I remember from my own scripture classes and in the church crèche being told about the wonderful sacrifices of the early Christian martyrs.”

[19] Barnes. D. Timothy, Constantine and Eusebius, P – 149-150 “But the Martyrs of Palestine no longer covered “the entire time of the persecution”; only in 313 could Eusebius undertake a definitive account of the whole decade of persecution. His first attempt utilized his earlier work. He rewrote the Martyrs of Palestine, abbreviating it to produce the short recension, which he incorporated in a second edition of the Ecclesiastical History. To the original seven books, slightly retouched (especially at the end), Eusebius now added two more. Book Eight comprised the rewritten Martyrs with a new preface for its context in the History,”

[20] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 262 “By imperial command God’s worshippers there perished wholesale and in heaps, some butchered with the sword, others fulfilled by fire; it is on record that with an inspired and mystical fervour men and women alike leapt on to the pyre.”

[21] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 263 “When these things were going on I was there myself, and there I witnessed the ever-present divine power of Him to whom they testified, our Saviour Jesus Christ Himself, visibly manifesting itself to the martyrs. For some time the man-eaters did not dare to touch or even approach the bodies of God’s beloved, but rushed at the others who apparently were irritating and provoking them from outside; only the holy champions; as they stood naked, and in accordance with their instructions waved their hands to attract the animals to themselves, were left quite unmolested: sometimes when the beasts did start towards them, they were stopped short as if by some divine power, and retreated to their starting point.”

[22] Croke, Brian. “The origins of the Christian world chronicle” in History and Historians in Late Antiquity, P- 126 “The Chronicle of Eusebius was a very intricate document and copying of its multi-coloured contents must have been very difficult. What happened, since the work was so popular and useful, was that the format was modified and simplified. At the same time the local chronicles and other records that had been maintained now won a new prominence. The Chronicle had made it possible to fit local history into the context of God’s time. Jerome’s translation is a good example of this. Not only did he update Eusebius to 387 but he built into it a larger number of notices relating to Roman history where Eusebius had been particularly thin.”

[23] Hamilton. Robert, “There is considerable discussion by scholars in regard to the Christian faith being essentially based on martyrdom, Jesus Christ was crucified and the cross became the churches main icon, and the fervour with which so many early Christians embraced the self-sacrificial act indicates this may be the essential attraction.* I suspect that the majority of early Christians were not part of the power elite and saw this religion as a way of escaping the brutal realities of their physical existence, under the Roman yoke, with a martyr’s death sending them into a far superior spiritual world.- heaven in fact.”

*Frend, W. H. C. “The failure of the persecution in the Roman Empire” Past and Present , 16: , 1959 , P-13 “Christianity he reminded his friend Ambrose, was a religion of martyrdom, and that singled it out as unique among the religions of mankind.”

[24] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 270 “thanks to the emperor’s humanity. Orders were then issued that eyes should be gouged out and one leg maimed. That is what they meant by ‘humanity’ and ‘the lightest punishments’ inflicted on us.”

[25] Grant, Robert McQueen. “The fifth theme: Persecution and martyrdom” in Eusebius as Church Historian , P-122 “When the persecution came on, Eusebius himself saw these shepherds ‘some shamefully hiding themselves here and there while others were ignominiously captured and mocked by the enemies’ (2.1). He has decided not to discuss either the pre-persecution squabbles or the persecution-time disasters. He does say, however, in V111 3 (Mart. Pal. 1. 3-4) that while many rulers of the churches kept the faith, there were many others who ‘proved weak at the first assault’.

[26] De Ste. Croix, G. E. M. “Aspects of the ‘great’ persecution” Harvard Theological Review , 47:2 , 1954 , P – 79“The time-honored method of deciding whether a given person was a Christian was the ‘sacrifice test’, as it will be called here: the individual concerned was asked to sacrifice, offer incense, or make a libation, to the gods or the emperor.”

[27] Grant, Robert McQueen. “The fifth theme: Persecution and martyrdom” in Eusebius as Church Historian , P-123 “Like Eusebius’ attitude, his own activities during the persecution may have seemed somewhat equivocal. The point was made by one of Athanasius’ supporters, the Confessor-Bishop Potammon, at the Council of Tyre in 335. ‘Tell me,’ he cried out to Eusebius,

‘Were you not in prison with me during the persecution? I lost an eye on behalf of truth, while you seem not to have any part of your body maimed. You were not a confessor but simply stood there, alive and without mutilation. How did you get out of prison unless because you promised the persecutors that you would do what is unlawful, or because you did it?’ “

[28] Hamilton. Robert “Very much like pacifists, and men who did not enlist, during the world wars of the twentieth century.”

[29] Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, P – 228 “It was a manifest visitation of divine providence, which became reconciled to the common people but took action against the perpetrator of these crimes, indignant with him as being primarily responsible for the whole iniquitous persecution.”

[30] Davies, P. S. “The origin and purpose of the persecution of AD 303” Journal of Theological Studies , 40:1 , 1989 , 66-94 “Lactantius states that the persecution of the Christians which broke out in the Roman empire in 303 was not of the emperor Diocletian’s choosing. It was instigated by his assistant Galerius, whom Lactantius presents as a pagan fanatic. Writing in Nicomedia in 313/14, Lactantius claimed that Galerius had held a series of secret conversations with Diocletian during the winter of 302/3, and in these conversations had gradually worn down the emperor’s resistance to persecuting the Christians; reluctantly and against his own judgement.”

[31] Lactantius, De Mortibus Persectorum, (trans – J.L. Creed) , P -19 “Diocletian had the kind of malice which consisted in acting without consultation when he had decided to do something good, so that he could get the credit himself, but in calling on a number of people for advice when he was planning something evil which he knew would merit censure, so that his own misdeeds could be blamed on others. So a few civil magistrates and a few military officers were brought in and questioned in order of precedence. Some, because of their own hatred of the Christians, expressed the view that they should be got rid of as enemies of the gods and opponents of the state religion; those who held a different view understood what the man’s wishes were and, through fear or a desire to please, expressed agreement with the opinion of the others.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cameron. Averil, The Mediterranean World In Late Antiquity, (second ed), Routledge, 2012.

Barnes. D. Timothy, Constantine and Eusebius, Harvard University Press, 1981.

Croke, Brian. “The origins of the Christian world chronicle” in History and Historians in Late Antiquity , Croke, Brian; Emmett, Alanna M. , 1983.

Davies, P. S. “The origin and purpose of the persecution of AD 303” Journal of Theological Studies , 40:1 , 1989.

De Ste. Croix, G. E. M. “Aspects of the ‘great’ persecution” Harvard Theological Review , 47:2 , 1954.

Eusebius, The History of the Church From Christ to Constantine, Book 8, (trans G.A. Wiliamson), Penguin Books.

Frend, W. H. C. “The failure of the persecution in the Roman Empire” Past and Present , 16: , 1959.

Average Rating