Plutarch, like many writers, told his audience what they wanted to hear. When comparing Plutarch’s account of the Osiris myth in his Isis and Osiris with the extant evidence from ancient Egypt, it is clear that the myth was a later development within the narrative of Egyptian religion. The textural evidence from the Egyptian civilisation represents a chronology over some three millennia from the Old Kingdom period up until the end of the Roman period. Egyptologists have found it useful to break up this enormous chronology into various sections; and this essay will analyse the extant information about the Osiris myth within the various established time periods. Plutarch, it is suggested, wrote his version of the myth around CE 120, at the latter stage of his own life. It is also constructive to keep in mind that all historians write in response to the issues of their own age when writing about the past. Plutarch’s reliability in recording the Osiris myth according to ancient Egyptian sources is particularly influenced by this fact. The cult of Isis was experiencing heightened popularity within the first centuries of the Imperial period of the Roman Empire; and this would have made the Osiris myth attractive to an author like Plutarch.[1] His decision to put the goddesses name first in the title may have been a savvy publishing move.

Plutarch’s Egypt Through Greek Coloured Glasses

Plutarch dedicates his account of the myth to someone called Clea, who, apparently, was a Priestess of Isis in Greece.[2] Plutarch himself, at this time, was now a Priest at Delphi; and these religious contexts are readily observable within his account of the Osiris myth. They are his motivation for writing Isis and Osiris; he is placing one of the major mythological strands of the Egyptian religious narrative within a wider conceptual paradigm of his own devising. This is strongly influenced by his Hellenism and adherence to the principals and pantheon of Greek philosophy and religion.[3] Plato is woven into this account, and his philosophy called upon to explain several key concepts.[4] Apart from Plato, as a source for Plutarch’s understanding of Egypt, he also calls upon Herodotus to explain folk lore and the etymology of certain words.[5] JG Griffiths, in his invaluable introduction and commentary to Isis and Osiris, informs readers that Plutarch also drew upon Homer, Hesiod, Simonides, Euripides, Anaxagoras, Aristotle, Cleanthes, Theodorus and Pindar.[6] Plutarch did, also, spend some time in Egypt. Plutarch is writing for a Graeco-Roman audience; and seeking to interpret the Osiris myth within that philosophical mindset.[7] The characters within the story are given Greek names, with Seth becoming Typhon, Thoth is Hermes, Osiris is alluded to be Dionysus, Isis linked to Persephone, and Horus called Apollo by the Greeks. In many ways, Plutarch the writer is taking raw material and moulding it into a story of his own conception, to serve his own ends; reliability and sticking to his sources seem the least of his concerns.

Aegyptus is the Greek Name for Egypt

“Osiris was born, and at the hour of his birth a voice issued forth saying, “The Lord of All advances to the light”. “[8]

Plutarch relates that Osiris was born on the first of the five “intercalated” days, which stand apart from the lunar calendar; and he invokes Zeus, Rhea and Cronus in his introduction to Osiris. Diodorus Siculus (90 BCE – CE 30), a near contemporary of Plutarchs, also wrote about Egypt, Osiris and Isis. Diodorus wrote in a similar vein to Plutarch about Osiris and Isis, again for a Graeco-Roman audience, placing their story in the context of the Greek gods, and relating parts of it to Dionysus and the mysteries surrounding this deity.[9]

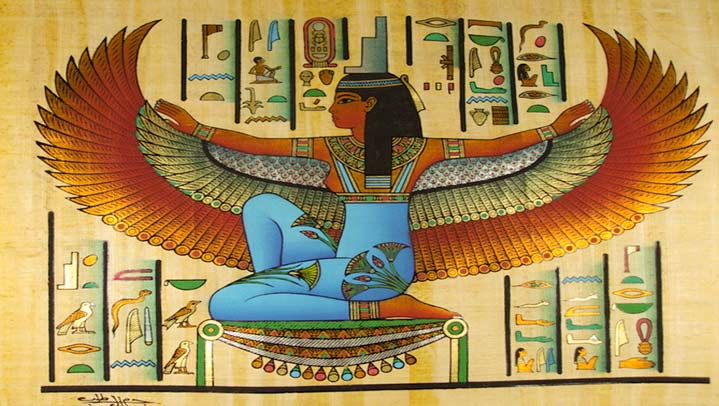

Plutarch tells his reader that “Isis is a Greek word”; her Egyptian name was actually Aset or Uset. There is an intellectual battle going on here, with Plutarch placing the cart = Greek culture, before the horse = Egyptian culture. He wishes his readers to be reassured that the Greek pantheon of gods precedes Egyptian conceptions of the divine, and is in the ascendancy when it comes to ideas about righteousness.[10] JG Griffiths described Plutarch in his study of the work as a “somewhat narrow Greek exclusivist”, quite rightly in my view.[11] The Ptolemaic influence on Egyptian culture was Hellenic and lasted for some three centuries, directly preceding the Roman era (30 BCE – CE 395).[12] The Coptic language, which began in the second century CE, is an Egyptian literary language that utilises the Greek alphabet. There is already a strong Hellenic influence over Egypt during the time in which Plutarch is alive and writing. This Greek view of ancient Egyptian culture and religion has remained until this day, and in many ways our perception of this civilisation is through Greek coloured glasses. The translation of hieroglyphs into ancient Greek, is Greek thought interpreting Egyptian culture. If we, today, are the inheritors of the Graeco-Roman traditions in western thought, philosophy, religion and government, then understanding the essence of ancient Egyptian culture and religion requires a conscious mind shift. Plutarch was not attempting this, quite the reverse, his Isis and Osiris is one of the early causes of our Graeco-centric view of Egypt. Aegyptus is the Greek name for Egypt, which was called Het-Ka-Ptah in the local language. Recent scholarship has sought to see beyond the ‘Greekness’ of our understanding of Egyptian religion and culture; Erik Hornung and Jan Assmann have been at the forefront of this. An examination of the extant texts from the various periods, in relation to the iconic evidence for Osiris, who he was and what roles, as a god, he served, may provide the material with which to compare Plutarch’s account of him.

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest known Egyptian texts and they date from the Old Kingdom period, the III to VI Dynasties (2686-2181 BCE). They are written upon the interior surfaces of the royal pyramids at Saqqara and comprise some 759 spells or utterances. A block from the V Dynasty, during the reign of King Djedkara, bears the head and upper torso of the god Osiris in human form.[13] The hieroglyphic symbols which designate Osiris’s name are the throne and the eye. This is thought to be the oldest extant appearance of Osiris; his iconography would emerge more fully as a human form wrapped in mummy bandages with his arms holding the sceptre of kingship, the crook and the flail. Osiris’s particular crown, called the ‘Atef’, has ram’s horns below a conical peak with a plume each side.[14] The Pyramid of Unas is the oldest of the pyramids and the text on the sarcophagus chamber on the south walls is inscribed with the text:

“O Unas, you have not gone dead, you have gone to sit on the throne of Osiris.”[15]

The fundamental role of Osiris, as indicated by the Pyramid Texts, is his symbolic connection with the dead king. Horus symbolises the new king and Osiris the departing king. There are repeated references to Osiris, and to Duat, the kingdom of the dead, that the funerary god oversees, within the texts inscribed on the Pyramid of Unas. Isis and Nephthys are also mentioned, as is Horus and Seth, and other gods like Geb, Atum and Re. The Pyramid Texts do establish a genealogy, or ennead, with Atum at the head, Shu and Tefnut directly below, Geb and Nut their progeny, and Osiris their eldest child with Isis, Seth and Nephthys (Thoth is sometimes included).[16] There is, in the words of JG Griffiths, “no coherent mythology” contained within the spells of the Pyramid Texts, only allusions to incidents involving the divine characters.[17] Such as the battle between Horus and Seth, and their physical collateral damage involving the loss of an eye and testicles respectively, and the restoration of these by Thoth. Isis at this time was not designated as the spouse of Osiris or mother of Osiris’s child, as she is in Plutarch’s later rendering of the myth.[18]

This lack of a mythic prose narrative within the Pyramid Texts has created disagreement and contention among Egyptologists, according to JE Hellum, as to whether any mythic religious element exists at all.[19] Jan Assmann sees the Pyramid Texts as “precursors to myth”, and Plutarch’s creation of Isis and Osiris, as the result of an evolutionary development toward mythic status.[20] This, in my view, renders the question of Plutarch’s reliability as somewhat irrelevant, as myth makers tend to write their own rules. John Baines points to a body of scholars, led by Heinrich Brugsch and Hermann Kees, who considered the fragmentary nature of the surviving Pyramid Texts, as not reflective of the existence of narrative myth within the ancient Egyptian civilisation.[21] VA Tobin mentions that there is some evidence within the Pyramid Texts for Osiris’s origins as a demon, which is something that Plutarch also stresses in his account of the Osiris myth.[22] The evidence to support Plutarch’s rendering of the Osiris myth, at this stage of the Egyptian chronology, is fairly inconclusive.

The Middle Kingdom period (2055-1773 BCE) produced what Egyptologists call the Coffin Texts, which are a collection of funerary spells inscribed on coffins. The role of Osiris as funerary god extends beyond royalty during this period, as evidenced by the Coffin Texts.[23] There is evidence, in the translation of Coffin Spell 148, that the Osiris myth has developed further in this period. This may reflect a closer affinity with some of the content of Plutarch’s account of the myth. Here mentioned for the first time is Isis, Osiris’s sister, being pregnant with the funerary god’s seed.[24]

“I am Isis, more spirit-like and august than the gods. There is a god within this body (womb) of mine and the seed of Osiris is he.”[25]

The Coffin Texts also make clear that it was Seth who killed Osiris in Gahesty on the bank of the Nedyet.[26] This part of the myth is also included in Plutarch’s account in generalised form.

The New Kingdom period, XVIII to XX Dynasties (1550-1069 BCE), is the most richly endowed with textural information that may have contributed to Plutarch’s account of the Osiris myth. The Stela of Amenmose: Hymn to Osiris contains many of the elements also included in Plutarch’s Isis and Osiris:

“Isis, the powerful, Protectress of her brother…Who received his seed and made his heir… The son of Isis, he has avenged his father… Evil has perished, the accuser is gone.”[27]

Jan Assmann summarises the myth of Osiris as “comprising a number of stories or constellations” involving a wife and her husband, rival brothers, and a mother and her son.[28] He acknowledges Plutarch, as first to collate all the strands of the story together into one “myth of Osiris”, but also identifies the iconographic form of the ancient Egyptian textural evidence. These funerary spells and incantations do not on their own make up a narrative, it takes an interpreter like Plutarch to mould them into something more palatable for a Greek thinking audience.

Plutarch, also, has something to say about the role of women, and husbands and wives through the Isis/Osiris myth.[29] His dedication of the work to Clea, and the Isis and Osiris story being part of a larger collection called Moralia, have a strong female focus.

The Book of the Dead is a product of the New Kingdom period, and could be seen as the apogee of the Osirian conception. According to Erik Hornung’s interpretation, chapter 154 of the Book of the Dead declares:

“ “decay” and “disappearance”, is claimed to await “every god, every goddess, all animals, and all insects”.”[30]

This distinct ancient Egyptian conception of death and its influence over the fate of its deities, marks it out as very different from the ancient Greek view of these things. This, in my view, makes it irreconcilable with Plutarch’s position as Priest of Delphi, within that religious framework and philosophy. Egyptian gods, and especially Osiris, are not immortal, as is the case with the Greek gods.

The Story of Horus and Seth, from the Papyrus Chester Beatty I, rto, tells a relatively lengthy version of the judging of Horus and Seth.[31] Plutarch reduces this to a concise one sentence in his version of the Osiris myth, right at the conclusion of his account of the myth itself.[32] It seems that this courtroom drama had no interest for Plutarch as a writer.

It can be concluded that it is pertinent to note that the majority of the textural evidence that remains from ancient Egypt, the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead, all directly relate to Osiris in his role as Lord of Eternity, the funerary god of the Duat. As has been clearly identified, there are allusions to elements contained within Plutarch’s account of the Osiris myth in the spells recorded in the various funerary texts from the ancient Egyptian time frames examined here. There is, however, no single source that includes all the strands of the story that Plutarch brings together in his Isis and Osiris. However, his surviving work is considered by history to be the most influential telling of this tale. Plutarch’s reliability as a historian, in regard to the content contained within the funerary texts that remain today, is a moot point, in my view. He is as much myth maker, as recorder of myths, as Jan Assmann has so clearly identified. Assmann and Hornung are interpreters of ancient Egyptian history for today’s world, whereas Plutarch performed a similar role for the Graeco-Roman world of the first centuries CE. Whether we are getting closer to a better understanding of this unique culture is debatable, in my view. It could be that JG Griffiths is correct in his assessment that it is, as impossible, for the modern anthropological scholar to grasp the polytheistic truth of the ancient Egyptians, as it was, for a religiously minded Plutarch to interpret Egypt’s pantheon of gods and goddesses objectively and without bias.[33]

©Robert Hamilton

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Assmann, Jan, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, (trans. David Lorton), (New York, 2001).

Baines, John, “Egyptian Myth and Discourse: Myth, Gods and the Early Written and Iconographic Record”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 01 April 1991, Vol 50 (2), pp. 81-105.

Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, (trans. C.H. Oldfather), Loeb Classical Library, Vol 1, Updated 5 Aug 2016, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/home.html viewed 2016.

Gilula, Mordechai, “Coffin Text Spell 148”, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 1 August 1971, Vol 57, pp. 14-19.

Griffiths, J Gwyn, “Isis and ‘The Love of the Gods’ “, Journal of Theological Studies, Jan 1 1978, Vol 29. Pp. 147-151.

Griffiths, J Gwyn, Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride, (Cardiff, 1970).

Frankfort, H, “Before Philosophy”, Antiquity, Vol 24, Issue 95, September 1950, pp. 156-158.

Hart, George, The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, 2nd ed, (New York, 2005).

Hellum, J.E., The Presence of Myth in the Pyramid Texts PhD (Toronto, 2001), http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp04/NQ59037.pdf viewed 2016.

Hornung, Erik, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt, (trans. John Baines), (New York, 1982).

Ockinga, BG (ed.) Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Macquarie University OUA AHIX 801 2010).

Plutarch, Isis and Osiris, (trans. FC Babbitt) Vol V, Loeb Classical Library ed of the Moralia (1936), (Updated Oct 2012) (ed. Bill Thayer) http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/home.html viewed 2016.

Pyramid of Unas, Pyramid Texts Online, (no date listed), Faulkner, Piankoff & Speleer (trans), http://www.pyramidtextsonline.com/translation.html viewed 2016.

Tobin, VA, “Myths” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, (Updated 2005), (ed. DB Redford), (Oxford, 2001) pp. 464-484. http://www.oxfordreference.com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/view/10.1093/acref/9780195102345.001.0001/acref-9780195102345-e-0485?rskey=SaHoQd&result=1 Viewed 2016.

[1] J Gwyn Griffiths, Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride, (Cardiff, 1970), p. 32.

[2] Plutarch, Isis and Osiris, (trans. FC Babbitt) Vol V, Loeb Classical Library ed of the Moralia (1936), (Updated Oct 2012) (ed. Bill Thayer) http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/home.html viewed 2016. p. 7.

[3] Op.cit., pp. 19, 31.

[4] Ibid, p. 32.

[5] Plutarch, Isis and Osiris, p. 13.

[6] J Gwyn Griffiths, p. 75.

[7] Ibid, p. 30.

[8] Ibid, p. 32.

[9] Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, (trans. C.H. Oldfather), Loeb Classical Library, Vol 1, Updated 5 Aug 2016, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/home.html viewed 2016 pp. 71-73.

[10] J Gwyn Griffiths, pp. 77-78.

[11] Ibid, p. 31.

[12] Plutarch, Isis and Osiris, p. 10.

[13] George Hart, The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, 2nd ed, (New York, 2005), p.114.

[14] Ibid pp.114-115.

[15] Pyramid of Unas, Pyramid Texts Online, (no date listed), Faulkner, Piankoff & Speleer (trans), http://www.pyramidtextsonline.com/translation.html viewed 2016. Utterance 213; 134.

[16] George Hart, p.115.

[17] Op. cit. p. 33.

[18] J Gwyn Griffiths, Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride, (Cardiff, 1970), p. 35.

[19] Hellum, J.E., The Presence of Myth in the Pyramid Texts PhD (Toronto, 2001), http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp04/NQ59037.pdf viewed 2016, pp. 13-15.

[20] Jan Assmann, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, (New York, 2001), pp. 95-96.

[21] Baines, John, “Egyptian Myth and Discourse: Myth, Gods and the Early Written and Iconographic Record”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 01 April 1991, Vol 50 (2), p.82.

[22] Tobin, VA, “Myths” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, (Updated 2005), (ed. DB Redford), (Oxford, 2001) pp. 464-484. http://www.oxfordreference.com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/view/10.1093/acref/9780195102345.001.0001/acref-9780195102345-e-0485?rskey=SaHoQd&result=1 Viewed 2016.

[23] George Hart, p.117.

[24] Gilula, Mordechai, “Coffin Text Spell 148”, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 1 August 1971, Vol 57, p. 14.

[25] Ibid, p. 14.

[26] George Hart, p.117.

[27] Text 8 (Stela of Amenmose: Hymn to Osiris), in BG Ockinga (ed.) Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Macquarie University OUA AHIX 801 2010).

[28] Jan Assmann, pp. 123-124.

[29] Griffiths, J Gwyn, “Isis and ‘The Love of the Gods’ “, Journal of Theological Studies, Jan 1, 1978, Vol 29. p. 149.

[30] Erik Hornung, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt, (trans. John Baines), (New York, 1982). p. 157.

[31] Text 43 (Stela of Amenmose: Hymn to Osiris), in BG Ockinga (ed.) Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Macquarie University OUA AHIX 801 2010).

[32] Plutarch, Isis and Osiris, p. 49.

[33] J Gwyn Griffiths, Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride, (Cardiff, 1970), p. 32.