The Grey Wolf in Ancient Rome

- Species Information –

Canis lupus.

Animalia, Chordata, Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae, Caninae, Canini, Canis, C. lupus.

Common name – Grey Wolf

The Grey Wolf is also known as the Arctic Wolf, Common Wolf, Mexican Wolf, Plains Wolf, Timber Wolf, and Tundra Wolf.[2]

The grey wolf is the largest canid and the males can weigh up to 60kg, with females typically 10-15% smaller.[3] Its coat colour can vary from agouti brown, pure white in the Antarctic, to black or a rusty colour. Physiologically the Grey Wolf has a large skull and teeth.

Found today in small pockets of North America, in northern Minnesota and the northern Rocky Mountains. Also, in small populations in the Iberian Peninsula, the Apennines in Italy, Turkey, and in south central Norway. And in Alaska and the Antarctic. Traditionally, the wolf inhabited all of North America, Eurasia and the Sinai Peninsula.

Wolves, typically, live in small groups of up to about six, they mate for life. When food is sparse they may live a more solitary lifestyle. Larger packs of wolves are usually of related families.

Status behaviour is thought to be derived around an alpha male, who exerts control through muzzling subordinates with his jaws. These wolves convey their submission by licking his muzzle as pups do to their mothers.

Reproduction occurs annually from March to July, depending upon latitude. Gestation is around 61-63 days. Pups are born effectively blind in an underground den. Between 2 and 3 weeks they open their eyes and make their way out of the den. All members of the pack feed the young with regurgitated food. The young fully mature after 2 years.[5]

The primary habitat of the Grey Wolf is open tundra and forest. Ungulates form the main part of the wolf’s diet, in particular deer. The fact that they are a predator on livestock has contributed to their almost total eradication from North America and Europe.

There is still much unknown about the behaviour of wolves in the wild.

- Archaeological Evidence –

When considering the Grey Wolf, it is important to remember that dogs are now considered to have evolved from Canis lupus. The earliest dog-like remains are thought to date from some 31 700 years ago and were discovered in the nineteenth century in Goyet Cave in Belgium.[6] There has not been universal acceptance of this find, as the earliest evidence of a dog-like creature, and the next nearest dated find is 14 000 years ago in western Russia.[7] Archaeological evidence points to dogs being domesticated at multiple places at different times. DNA analysis, on the other hand, of some 1500 dogs in the Old World, led researchers to conclude that all these dogs had their ancestors domesticated some 16 300 years ago in China, south of the Yangtze River.[8]

In a brief interview with my local veterinarian, Dr Alan Mills of Vets Victor Central, I raised the fact, discovered through my research, that all breeds of modern dogs are descended from the grey wolf.[9] Dr Mills confirmed this, and shared with me his personal insight into this phenomenon, through his dental work on canines in his practice. He stated that despite the breeding programs over decades and centuries, which have resulted in much smaller breeds of dogs in terms of physical size, their teeth and jaws remain prodigious in relation to the rest of the body. This often causes dental health problems in smaller breeds of dog, according to Dr Mills. We agreed that this part of the dog had not evolved as greatly, and retained similarities through the jaw and teeth with the wolf.

- Role in Daily Life –

The wolf is a wild animal and a carnivore, and thus was viewed as a predator of livestock in Roman times. Although, wolves were hunted in Roman times, they were not an especially popular choice as prey for hunters. Whether this had something to do with the place of the wolf in Roman myth and culture, or was more linked to the difficulty and expense involved in hunting wolves is not immediately clear from the literature. Nets and hunting dogs were used to trap and capture, and/or kill prey like wolves. Wolves were hunted primarily for their pelts and not for their meat. Dogs were sacrificed on occasion in ancient Rome and the meat of puppies eaten quite regularly.[10]

Wolves do not feature in venationes, and it is thought that this is due to the difficulty in capturing them alive, and getting them to act in the arena according to the scripted activities.[11]

Charles Hamilton-Smith states in his book, The Natural History of Dogs:

“ “Nullos fovet Brittania” (lupos) is a quotation from Textor, cited by Gesner; and it is probable that the Romans laboured to clear the island of them.”[12]

The wolf in everyday life is hated by the farmer, hunted for sport by men with high tech rifles for the fun of it, and rarely seen by the vast majority of human beings who live in urban settings. The wolf is, quite rightly, secretive, because it is constantly under threat from humanity. Only, animal experts and naturalists, who like to study and film animals in the wild actually get to observe these animals. Conservationists are also usually supporters of wildlife, if they are located in their idea of the correct habitat.

- Representations in Art –

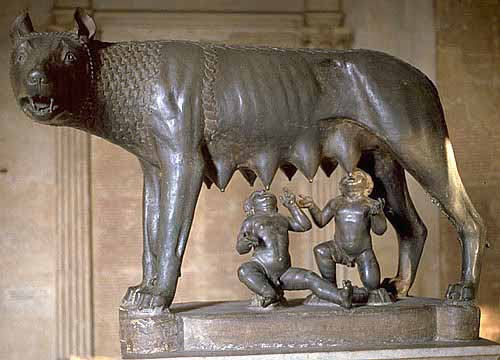

The wolf’s presence as Lupercale, she-wolf wet nurse to Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, assures the wolf’s place in the artistic frame of Ancient Roman culture. Indeed, this powerful bi-species image still fascinates artists today. The wolf is both mother and/or wet nurse to Rome, and related to Mars the God of War. The wolf is depicted in art as a fierce and intelligent creature, and most often as a she-wolf.

The bronze statue of a she-wolf, which is the symbol of the city of Rome, was originally thought to be a 5th century BCE Etruscan statue, to which Antonio del Pollaiolo added the twins in the 15th century. Now, however thanks to the work of art historian, Anna Maria Carruba, it is considered to be far more likely a product of the 11th or 12th centuries CE.[14] The she-wolf in the act of nurturing the twins can be seen in many buildings as a homage to Rome: this scene is called Lupercale or Natale di Roma (Roman Christmas).

She-wolves in Corso Francia (left) and in a building near S. Maria Maggiore (centre); dog at the entrance of Biblioteca Casanatense (right)

A Bronze wolf’s head from the 1st Century CE.

Unattributed Artist.

The wolf was symbolically represented in the Roman military in the earliest Aquilas, which were carried by Aquilifers, the standard bearers of a legion.[18] These ranking soldiers would often wear a wolf’s pelt or bear’s belt. Eventually all the Aquilas became eagles, around the first century BCE.

The she-wolf in art has an added sexual dimension; and the wolf and female sexuality have been linked ever since. Think of the psychological themes underpinning the story of Little Red Riding Hood, with their allegorical allusions to emerging sexuality communicated via the carnality of the tale. Perrault’s original seventeenth century title was Red Cap, and that name has allusions to the clitoris and the deflowering of virginity.[20] It is in many ways, a traditional folk story about the coming of age, which has been turned into a more prudish warning of the dangers men pose to young girls. The wolf is a carnal beast and much blood is spilt, echoing the breaking of the hymen during first penetration.

- References in Texts –

The Romulus & Remus Foundation Myth of Rome

The wolf, and in particular the ‘she-wolf’ is powerfully linked to the founding myth of the ancient city of Rome itself. The legend of Romulus and Remus being suckled by the she-wolf dates back to around 300 BCE.[22] Ovid in his Metamorphoses gave Quirinus, one of Rome’s archaic triad of gods, a mythological role by equating him with Romulus, the founding hero of Rome.[23] This created a genealogy for Quirinus, and made him the son of Mars in the Hellenised pantheon of Roman gods.

Virgil in his Aeneid, has:

“Ilia, heavily pregnant, will carry twins for Mars.

Next Romulus will continue the race, taking pride in his nurse

The tawny skin of a she-wolf, and found the walls of Mars.

He will call the people from his own name, Romans.”[24]

Virgil thus directly links Rome with Homer’s Iliad, the greatest literary influence in the Hellenistic world, as the descendants of the Trojans make their way to the place where they will create the most powerful city on Earth. As a founding mythology it neatly inserts the Julian gens, Augustus’ family name, into its rightful place as the rulers of Rome from the very beginning; and provides them with another god, Mars, in their genealogy.[25] The motif of the wolf suckling the twins was frequently depicted on coins and altars by later Roman Emperors. Associations with Mars and Hercules are also suggested on some coins. The Romans, unlike the Egyptians, did not worship the wolf, but rather attributed wolf-like qualities to the city of Rome.

There was no consensus among the ancient writers, when it came to just how Rome was founded. Dionysius of Halicarnassus stated that there were many different versions of the story, but most of them did include the Trojan link and somebody called Romulus.[27] The founding myths that included the twins Romulus and Remus, and their mother Ilia, who was made a vestal virgin by her wicked uncle Amulius, but was impregnated by the god Mars, and the twins were taken from her to be exposed by the river Tiber to die, were the most popular with the Roman people. There on the banks of the river the twins were found by a wolf, who suckled then until they were rescued by a shepherd.[28] The twins later discover that their mother was the rightful daughter of the true king of Alba Longa, Numitor, and that they are the heirs of the throne. Rome is later founded on the exact spot where the wolf suckled the twins. Romulus kills his twin brother Remus in competition over where the city should be established.

Cristina Mazzoni makes an interesting word correlation when she points out in her book, She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon, the word ‘troia’ in Italian can describe a female animal, a sow, but that it is also a derogatory slang term for a female prostitute. Which is fairly run of the mill male misogynistic language; but interestingly if that word is capitalised as “Troia’, it becomes the Homeric ancient city of Troy.[29] Thus linking to the tale of the twins and the founding of Rome.

Further Wolf References in Roman Texts

Pausanias tells the story of the Ghost of Temesa, Lycas, who wore a wolf skin and “his whole appearance was most dreadful”.[30] Emeline Richardson lists the appearance of wolf- like characteristics in the villains and monsters from ancient texts, and plots the emergence of the werewolf; which inhabits our scary stories to this day. She states that the wolf was Apollo’s creature in Greek antique culture, and was the bringer of death.[31] In Italy, the wolf is more often associated with the war god Mars; who was worshipped by the Samnites and Umbrians, as well as the Romans.[32] Livy is cited by Richardson as recounting the story of the wolf as a positive omen for the Romans before the battle of Sentinum in 295 BCE.[33] The Etruscans associated the wolf with the underworld, as a number of ‘wolf-demons” are carved on “Hellenistic ash urns from Perugia and Volterra”.[34] Here the evolutionary relationship between the wolf and the dog must be acknowledged, particularly in relation to its role as protector of the underworld. The wolf represents the archetypal wild animal in many ways, and remains with us in Western folk tales today like Little Red Riding Hood, as the “big bad wolf”.[35] As the Romans were essentially an agrarian culture, wild animals were viewed as threats to both livestock and their human masters. The wolf and its many ungulate forms of prey would not be an endearing relationship within the Roman agrarian paradigm.

6.Role in Religion –

The Lupercalia, or “Wolf Festival”, is a pagan/pastoral celebration, which is pre-Roman. This ancient fertility and purification festival occurred around the Ides of February, 13 to 15; and is thought to have replaced an earlier festival of a similar nature called Februa. Lupus being Latin for wolf, hence the etymology of the name Lupercalia. There is a connection with the Greek God Pan, who it has been suggested morphed into the Roman god Faunus within Roman culture.[36] Plato in his Phaedrus has Socrates mentioning that the festival was introduced into Italy by Evander prior to the existence of Rome.[37]The pastoral/fertility aspect of the festival has Lupercus, Roman god of shepherds involved; and the Luperci, who were priests of Faunus, dressed in goatskins, and directing sacrifices of goats and dogs. Wiseman informs the reader that Roman literary source M. Terentius Varro explains the name of the Luperci by vent of circular rationale, that they are so-called because they sacrifice at the Lupercalia.[38] What Wiseman is inferring here is that the identity of the god Lupercus is somewhat shrouded in generalities; as is the entire founding myth of Rome itself. Patrician Luperci were initiated with an anointment of sacrificial blood on their foreheads, which was transferred from the bloody knife with wool dipped in milk. After the sacrificial feast was completed, the Luperci would cut thongs from the skins of the dead animals, and in imitation of the god Lupercus, would run naked through the Palatine city striking people near them.[39] Young women would line up to receive the blows, as they were thought to encourage fertility. The Ficus Ruminalis, a particular fig tree on the banks of the Tiber, is apparently the exact location where the she-wolf suckled the twins and the start and finish location of the Lupercalia run through the old city.[40]

This festival had an overt sexual flavour to it. In Rome in 276 BCE, according to Wiseman, Orosius reports an epidemic of miscarriages and still-births, and this is when the Lupercalia flagellation was introduced as recorded by Livy.[41] Ovid colourfully recounts that young men and women were ripe “terga percutienda dabant” for sex with each other. Fertility rites and celebrations were often accompanied by the drinking of alcohol and other Dionysian practices. Inebriation was often followed by copulation in the spirit of many fertility/spring festivals. The wolf as predator of the shepherd’s flock of goats, has a sexual connotation, as the heightened nature of the sexual act retains psychological parallels with the hungry feeding of wolves. Male sexual penetration has metaphorical links to the sacrificial knife; and the slaughtering of the innocent lamb is somehow akin to rape or the deflowering of the virgin. Wiseman states that the Roman god Inuus was the god of sexual penetration.[42] Inuus was involved in the Lupercalia through his connection with a Lycaean Pan and the possible Arkadian origin of the festival itself.

The she-wolf herself has become a metaphor, also for female sexual appetite and/or power. Lupa became a slang word in Latin word for prostitute in the ancient world. The animal nature of sexuality has always led human beings to associate that part of their behaviour with the animal kingdom. A woman who makes her living by having sex, was obviously thought to inhabit that animal, wolf-like, identity.

The Christianisation of the Roman Empire created many difficulties for the church and state authorities in their sanctioning of traditional festivals like the Lupercalia; which enjoyed great public support as they were days of fun and celebration. In the fifth century CE the Pope Gelasius 492-496 CE is attributed as the author of Against Andromachus and the Other Romans who Hold that the Lupercalia should be Celebrated According to Ancient Custom, where the conflicting old ways are taken to task by the Priest of Rome over what is now viewed as scandalous public behaviour.[43] Cult has become carnival; the she-wolf is no longer officially worshipped in Rome and has been replaced by the cross.[44] Naked men running through the streets beating women, whilst onlookers laughed was no pleasing Christian visage.

The wolf, through its association with the pagan festival Lupercalia and its sexual nature, has, via the Christianisation of the Roman world and of the Western world after that, been demonised. The wolf and its carnality has come to be associated with the Devil. The spirit and the ethereal are good, and the body and its fleshly desires are bad, under the aegis of Christian dualistic philosophy. The hairy god Pan and his Priapus are symbolic of the animal world, all that is lower and thus evil. When in fact the wolf, like all animals, is merely natural. The abusive paedophilia of celibate priests can be seen as a direct reaction to the unnatural denial of the body’s sexual function. Are they not wolves in sheep’s clothing?

7.Conclusion

The wolf held a very special place within ancient Roman culture and mythology. The she-wolf, as seen in the City of Rome’s founding myth, was wet nurse to Rome’s founder Romulus and his brother Remus. The Lupercalia is an ancient pastoral festival, which celebrates fertility and purification. The Roman god Lupercus is most often depicted as wolf/dog; and the festival itself became a dual celebration of both the founding of Rome, with its links to the she-wolf, and the older spring/fertility festival. The wolf was demoted by Christianity from founding mother to demon, in the West’s dominant religious philosophy of the last two millennia. The shepherd protects his flock from the predator, the wolf, and this motif runs through the Christian allegorical parables, tainting the wolf with evil. The innocence of the lamb is held up as an ideal state by Christianity, not the cunning intelligence of the wolf.

The wolf is the direct ancestor of all modern dogs; and the dog’s relationship to human beings must be considered as the closest of all our relationships with other animals. The dog is the domesticated wolf; and somewhere back some 30 000 years ago a wild animal forged a new relationship with one of the few animals that could claim it as prey. The grey wolf cannot be viewed in its entirety without honouring the special relationship between human and dog. The sheer variety of different types of modern dog breeds is quite incredible; especially when we know they all are descended from the grey wolf. German Shepherds remain very close in size and appearance to the grey wolf, but many other dog breeds, externally, bear no resemblance, except they all share the wolf’s jaw and teeth.

In art and literature, the wolf has morphed into an iconic symbol of both sexual appetite and supernatural carnality. Little Red Riding Hood’s big bad wolf and the werewolf share equal top billing in the collective subconscious’ of modern human beings. Sexual predator and the undead’s savage beast roam the shadowy recesses of our fearful thoughts. In part, I think this is due to the mysteriousness of the wolf in the wild; according to the literature on the subject we still do not know a great deal about the natural life of the wolf.

Wolves have been hunted to the point of extinction in much of North America and Europe. High tech weapons have made that job much easier for hunters and farmers. Humanity’s carnivorous taste for livestock will see the wolf remain on our hit list, as long as the wolf threatens the lives of the animals we farm for profit and eat ourselves.

©Robert Hamilton

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Http://Archive.Archaeology.Org/1009/Dogs/

“Http://Www.Canids.Org/Species/View/Prekld895731.”

“Http://Www.Ladywoods.Org/Index.Php/Wheel-of-the-Year-Imbolc/18-Wheel-of-the-Year-Imbolc.” Last modified Accessed.

“Http://Www.Romeartlover.It/Bestiario.Html.” Last modified Accessed.

“Http://Www.Slowitaly.Yourguidetoitaly.Com.” Last modified Accessed.

“Http://Www.Sorcery.Yuku.Com.” Last modified Accessed.

“Https://Au.Pinterest.Com/Ottonueve/Ancient-Roman-Character/.” Last modified Accessed.

“Https://En.Wikipedia.Org/Wiki/Gray_Wolf

“

Last modified Accessed.

Germonpre, Mietje. “Fossil Dogs and Wolves from Palaeolothic Sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, Ancient DNA and Stable Isotopes.” Journal of Archaeological Science 36, no. 2 (2009): pp 473-90.

Hamilton-Smith, Charles. The Natural History of Dogs. London: W.Curry, jun. and Company Dublin, 1839.

Jardine, William. The Naturalist’s Library. Vol. 9. London: Lizards, 1839.

King, Anthony. The Natural History of Pompeii. Edited by Wilhemina Feemster Jashemski. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Malcolm, James, Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia

Detroit: Gale, 2003.

Mazzoni, Cristina. She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

McLynn, Neil. “Crying Wolf: The Pope and the Lupercalia.” The Journal of Roman Studies 98 (2008): pp 161-75.

Mills, Dr Alan. Veterinarian Victor Harbor Vet ed., 2016.

Orenstein, Catherine. Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Plant, Ian. Myth in the Ancient World. South Yarra: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Richardson, Emeline. “The Wolf in the West.” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 36 (1977): pp 91-101.

Shelton, J. “Elephants as Enemies in Ancient Rome.” Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 32, no. 1 (2006): pp 3-25.

Thalmann, O. “Http://Science.Sciencemag.Org/Content/342/6160/871.” Science 342 (2013): pp 871-74.

This didrachm, minted in Rome between 269-266 BCE, is the first example of the she-wolf appearing on coinage. Interestingly, though this coin was minted in Rome, it is a Greek unit of currency. “Http://Www.Dartmouth.Edu/~Art2artifact/Gilsdorf/Sym04.Html.” Last modified Accessed 27 May, 2016.

Tsuyachan. “Http://Tsuyachan.Deviantart.Com/Art/Fanart-Little-Red-Riding-Hood-and-the-Wolf-464649521.” Last modified Accessed 27 May 2016.

Unattributed. “Confirmed: Capitoline Wolf Is Medieval(Romanesque) Not Etruscan.” Peregrinations Journal of Medieval Art & Literature IV, no. 1 (2013): pp 1-2.

Virgil. Aeneid.

Wiseman, T.P. “The God of the Lupercal.” Journal of Roman Studies 85 (1995): pp 1-22.

[1] Figure 1.”Http://Www.Canids.Org/Species/View/Prekld895731,” recorded.

[2] http://www.arkive.org/grey-wolf/canis-lupus/

[3] Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia

2nd ed., s.v. “Dogs, Wolves, Coyotes, Jacklas, and Foxes (Canidae).” p 276

[4] Figure 2. Black and white-furred gray wolves, n. d. photograph, viewed 19 May 2016, “Https://En.Wikipedia.Org/Wiki/Gray_Wolf

“

accessed.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray_wolf

[5] Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia

p 277

[6] Http://Archive.Archaeology.Org/1009/Dogs/

[7] Mietje Germonpre, “Fossil Dogs and Wolves from Palaeolothic Sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, Ancient DNA and Stable Isotopes,” Journal of Archaeological Science 36, no. 2 (2009). http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440308002380

[8] O. Thalmann, “Http://Science.Sciencemag.Org/Content/342/6160/871,” Science 342 (2013). abstract

[9] Dr Alan Mills, Veterinarian Victor Harbor Vet ed. (2016).

[10] Anthony King, The Natural History of Pompeii, ed. Wilhemina Feemster Jashemski (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002). p 414

[11] Ibid. p 415

[12] Charles Hamilton-Smith, The Natural History of Dogs (London: W.Curry, jun. and Company Dublin, 1839). p 153

[13] “Http://Www.Slowitaly.Yourguidetoitaly.Com,” accessed.

[14] Unattributed, “Confirmed: Capitoline Wolf Is Medieval(Romanesque) Not Etruscan,” Peregrinations Journal of Medieval Art & Literature IV, no. 1 (2013). p 1

[15] “Http://Www.Romeartlover.It/Bestiario.Html,” accessed.

[16] “Http://Www.Sorcery.Yuku.Com,” accessed. Bronze wolf’s head 1st Century CE.

[17] “Http://Www.Ladywoods.Org/Index.Php/Wheel-of-the-Year-Imbolc/18-Wheel-of-the-Year-Imbolc,” accessed. Unattributed Artist

[18] William Jardine, The Naturalist’s Library, vol. 9 (London: Lizards, 1839). p 142

[19] “Https://Au.Pinterest.Com/Ottonueve/Ancient-Roman-Character/,” accessed.

[20] Catherine Orenstein, Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked (New York: Basic Books, 2002). p 23

[21] Tsuyachan, “Http://Tsuyachan.Deviantart.Com/Art/Fanart-Little-Red-Riding-Hood-and-the-Wolf-464649521,” accessed 27 May 2016.

[22] Cristina Mazzoni, She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). p 1

[23] Ian Plant, Myth in the Ancient World (South Yarra: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). p 117

[24] Virgil, Aeneid. 1. 274-277

[25] Plant, Myth in the Ancient World. p 122

[26] minted in Rome between 269-266 BCE This didrachm, is the first example of the she-wolf appearing on coinage. Interestingly, though this coin was minted in Rome, it is a Greek unit of currency, “Http://Www.Dartmouth.Edu/~Art2artifact/Gilsdorf/Sym04.Html,” accessed 27 May, 2016.

[27] Plant, Myth in the Ancient World. p 123

[28] Ibid. pp 123-124

[29] Mazzoni, She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon. p 1

[30] Emeline Richardson, “The Wolf in the West,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 36 (1977). p 91

[31] Ibid. p 94

[32] Ibid. p 93

[33] Ibid. p 94

[34] Ibid. p 95

[35] J. Shelton, “Elephants as Enemies in Ancient Rome,” Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 32, no. 1 (2006). p 4

[36] T.P. Wiseman, “The God of the Lupercal,” Journal of Roman Studies 85 (1995). p 4.

[37] Neil McLynn, “Crying Wolf: The Pope and the Lupercalia,” The Journal of Roman Studies 98 (2008). p 162

[38] Wiseman, “The God of the Lupercal.” p 1.

[39] Ibid. p 6

[40] Ibid. p 7

[41] Ibid. p 14

[42] Ibid. p 6

[43] McLynn, “Crying Wolf: The Pope and the Lupercalia.” pp 162-163

[44] Ibid. p 163